Challenging Discourses of Food Insecurity

Dr. Kellie McNeill challenges dominant discourses on food insecurity in the Departmental Seminar Series at the University of Auckland, including the neoliberal and charity discourses. The Menu of Myths reveals how these discourses perpetuate the problem rather than solve it.

- Uploaded on | 0 Views

-

bettiplate

bettiplate

About Challenging Discourses of Food Insecurity

PowerPoint presentation about 'Challenging Discourses of Food Insecurity'. This presentation describes the topic on Dr. Kellie McNeill challenges dominant discourses on food insecurity in the Departmental Seminar Series at the University of Auckland, including the neoliberal and charity discourses. The Menu of Myths reveals how these discourses perpetuate the problem rather than solve it.. The key topics included in this slideshow are . Download this presentation absolutely free.

Presentation Transcript

1. Let them eat cake: challenging the dominant discourses of food insecurity Let them eat cake: challenging the dominant discourses of food insecurity Dr Kellie McNeill Department of Sociology University of Auckland Departmental Seminar Series 9 April, 2014

2. Menu of Myths Menu of Myths Food insecurity in Aotearoa? Surely not! The best of intentions: the charity discourse Shooting the messenger: the public nutrition discourse Jo and Jolene Client (ne Citizen): neoliberal discourses

3. What is Food Insecurity? What is Food Insecurity? FAO (1996) on food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life USDA on food in security: limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways " Within the context of wealthy western nations food insecurity means people are: at times, uncertain of having, or unable to acquire, enough food for all household members because they had insufficient money and other resources for food (Nord, Andrews & Carlson, 2009, p.2).

4. Talking with Their Mouths Half Full Talking with Their Mouths Half Full The qualitative aspect of the research sought to understand: The experience and implications of food insecurity Peoples strategies for addressing foodlessness and hunger The impacts of food security on peoples lives Rationale: Limited micro level qualitative accounts in NZ Social Services report levels of service provision (e.g. number of food parcels) and profile typical client groups depoliticises the issue/no examination of macro causality Public health frameworks use quantitative descriptions to report on nutritional implications neglect social implications

5. Key Findings Key Findings There are many myths about why people experience food insecurity poor budgeting and spending choices, low levels of life skills The experience of food insecurity is often borne out in secrecy because of the stigma attached to it as a symptom of poverty and poor choices Food insecurity contributes to social exclusion and marginalisation diminished citizenship The public nutrition discourse compounds the experience of deprivation that accompanies food insecurity The priority concern for respondents was avoiding or alleviating hunger NOT nutrition The achievement of food security ALWAYS interacts with political economy

6. 1. The Charity Discourse 1. The Charity Discourse

7. Plenty and Want in Godzone? Plenty and Want in Godzone? National Nutrition Surveys consistently report that around 20% of New Zealand households with children were impacted by some level of food insecurity (Russell, Parnell & Wilson 1999; Ministry of Health 2003). Over 15% percent of SoFIE respondents (n=18,950) were food insecure in 2004/05 Accepted figure across the general NZ population = about 10% are affected by some level of food insecurity, which has also been found to have a positive association with: sole parenthood, unmarried status, younger age groups, M ori and Pacific ethnicity, worse self-rated health status, renting, being unemployed and lower socioeconomic status. In multivariate modelling Income was the strongest predictor (Carter, Lalumata, Kruse & Gorton, 2010).

8. Hamilton Food Aid Results Hamilton Food Aid Results A census style survey of Hamilton food aid services showed that over a 12 month period in 2005/2006 this very average NZ community of around 130,000 people absorbed: $1,157,623 worth of SNG for Food (WINZ) 4,232 food parcels, each with enough food to feed a household for three days 25,557 community meals

9. The best of intentions The best of intentions Other than the SNG for Food, food aid in NZ is not state funded WINZ and DHBs regularly refer people to food banks and community meals The charity sector has been written in to NZs welfare policies as a response to food insecurity Charity food aid is largely overseen by faith based organisations Religious imperative to feed those in need relieves the state from fully recognising the right to food as a human/citizenship right

10. 2. Shooting the Messenger 2. Shooting the Messenger Food insecurity and hunger are accompanied by subjective experiences of deprivation and stigma People attempt to alleviate their sense of deprivation by rationalising nutritional disruption Nutritional disruption becomes entrenched and resistant to public nutrition information Public nutrition information compounds the experience of deprivation

11. Food Insecurity, Deprivation and Stigma Food Insecurity, Deprivation and Stigma The whole food [insecurity] thing can just put you in a very different space from other people, especially from those ones whodont really get it. No one likes missing out sort of feeling like they cant enjoy life in the same way as other people. Ive been thinking about this a lot with the situation Ive been in, and in my experience food can be a really big thing when it comes to showing up those kinds of differences. (Meredith) I guess you just dont want to be seen as not coping, and you dont want to feel like youre not coping. You kind of just work at keeping things looking good from the outside looking in. Youre doing your best, you know. And when youre doing your best and still not cutting it, then you dont really want other people rubbing your nose in it. (Sheryl)

12. Food insecurity and hunger are accompanied by subjective experiences of deprivation and stigma People attempt to alleviate their sense of deprivation by rationalising nutritional disruption Nutritional disruption becomes entrenched and resistant to public nutrition information Public nutrition information compounds the experience of deprivation

13. Rationalising Disrupted Nutrition Rationalising Disrupted Nutrition People have got it wrong when they say you need three meals a day. No, that three meals a day thing thats crap. I look at it like this for me. I tell myself that I havent done a hard days work, so what have I got to be hungry for? (Wayne) In a way, Im just living healthier thats all it is. Im eating in smaller portions, so really Im just eating consistently healthier. And you just dont really need the range of elaborate foods that everyone thinks you do But Ive been forced to think like that, which is kind of fucked actually. Its rather...depriving. (Christina) I think to myself that part of the reason that Im fasting is that I want to master the hold and the addiction that my body has on food. (Sandy)

14. Food insecurity and hunger are accompanied by subjective experiences of deprivation and stigma People attempt to alleviate their sense of deprivation by rationalising nutritional disruption Nutritional disruption becomes entrenched and resistant to public nutrition information Public nutrition information compounds the experience of deprivation

15. Entrenchment of Disrupted Eating Entrenchment of Disrupted Eating Its normal for me to just have one meal a day. Thats my reality and Im happy with thatNow that meal could be breakfast, lunch or tea but for me its just that meal a day In the evening I fill the time with cups of tea and coffee if Im hungry. Just hot drinks. I drink hot water occasionally. (Wayne) Im sort of in a routine with the situation where I make a conscious decision and say to myself, Right. This is where were at. Im going to fast, and Ill just take fluids for the day... When Im fasting Im preserving food to meet my sons needs. I will avoid doing the food because I know that there will be enough for him if I go without. (Sandy) I miss them [lunch and breakfast] altogether and just have dinner. Dinner is my main meal. I find that when Im working I dont eat as much. It keeps me busy and spares me a meal I just go and have a cigarette and a cup of tea and thats it Im back in there. (Rob) I dont usually eat until night time. If foods running low I cut that evening meal out as well. Or Ill have something thats not a balanced meal. Like a sandwich or something. That happens more often than not. I quite often have a coffee instead of an evening meal. (Faye)

16. Nutrition Interrupted Nutrition Interrupted you quite often sort of end up just kind of concentrating on dealing to the hunger side rather than thinking too hard about what it is youre actually eating. (Wayne)

17. Food insecurity and hunger are accompanied by subjective experiences of deprivation and stigma People attempt to alleviate their sense of deprivation by rationalising nutritional disruption Nutritional disruption becomes entrenched and resistant to public nutrition information Public nutrition information compounds the experience of deprivation

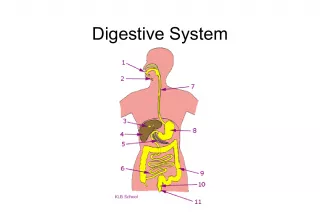

18. The Social Marketing of Nutrition The Social Marketing of Nutrition

20. Compounding the Experience Compounding the Experience Examining the problem of food insecurity from a health and public nutrition paradigm assumes that: The health and nutrition consequences of the experience are paramount Poor nutrition is the result of poor food choices The best intervention measure to address poor nutrition is targeted social marketing Food insecure people employ a range of strategies to address their situation. The public nutrition message stigmatises many of these as bad rather than rational The effectiveness of public nutrition campaigns is limited because the approach taken does not match the lived realities of many members of their target audiences = chronic policy failure

21. 3. Neoliberalism: Clients or Citizens? 3. Neoliberalism: Clients or Citizens? The language of New Public Management has been widely adopted within both state and NGO apparatus The residual welfare state means testing versus universality Soft residualism also adopted by the charity sector Growth of food insecurity among the working poor Assignment of blame at the individual level implies that food insecurity is an outcome of poor choices rather than structural conditions

22. Food Insecurity a Wicked Problem Food Insecurity a Wicked Problem The classical systems approach is based on the assumption that a planning project can be organised into distinct phases: understand the problem, gather the information, synthesize the information and wait for the creative leap, work out solutions and the like. For wicked problems, however, this type of scheme does not work. (Rittel & Webber, 1973, p. 161) Broadening the existing range of expert stakeholders to include those who talk with their mouths half full opens up opportunities to develop definitions of the problem of food insecurity grounded in first-hand experiences that could more helpfully direct future re-solutions

23. Food is an important part of a balanced diet (Fran Lebowitz) k.mcneill@auckland.ac.nz

24. References References Carter, K., Lalumata, T., Kruse, K., & Gorton, D. (2010). What are the determinants of food insecurity in New Zealand and does this differ for males and females? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health , online. McNeill (2011). Talking with Their Mouths Half Full: food insecurity in the Hamilton community. [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Waikato, New Zealand. Ministry of Health. (2003). NZ Food NZ Children: findings of the 2002 National Children's Nutrition Survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Nord, M., Andrews, M., & Carlson, S. (2009). Household Food Security in the United States, 2008: Economic Research Report Number 83. USDA Economic Research Service. Russell, D., Wilson, N., Parnell, W., & Faed, J. (1999). Key Results of the 1997 National Nutrition Survey. Ministry of Health. Wellington: Ministry of Health.