ICT2191 Topic 6 - Knowledge Representation and Rule-Based Systems for Steering Around Obstacles

This topic covers the basics of knowledge representation and some formalisms, as well as the use of rule-based systems for synthesising movement to

- Uploaded on | 1 Views

-

giuseppina

giuseppina

About ICT2191 Topic 6 - Knowledge Representation and Rule-Based Systems for Steering Around Obstacles

PowerPoint presentation about 'ICT2191 Topic 6 - Knowledge Representation and Rule-Based Systems for Steering Around Obstacles'. This presentation describes the topic on This topic covers the basics of knowledge representation and some formalisms, as well as the use of rule-based systems for synthesising movement to. The key topics included in this slideshow are . Download this presentation absolutely free.

Presentation Transcript

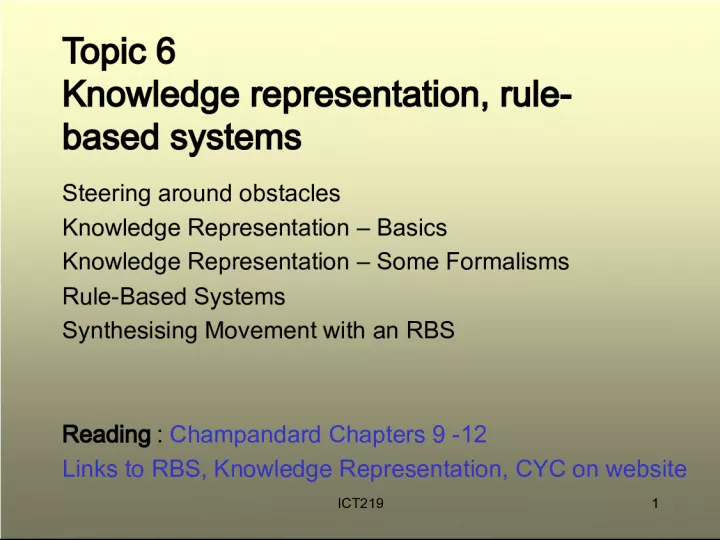

Slide1ICT2191 Topic 6 Knowledge representation, rule- based systems Steering around obstacles Knowledge Representation – Basics Knowledge Representation – Some Formalisms Rule-Based Systems Synthesising Movement with an RBS Reading : Champandard Chapters 9 -12 Links to RBS, Knowledge Representation, CYC on website

Slide2ICT2192 Steering Around Obstacles • Continuing to develop our obstacle-avoidance code for FEAR animats, Champandard uses the concept of steering behaviours (Reynolds, 1999) • Assume an animat which can move (using a locomotion layer). Assume a physics system which has friction and obeys Newtonian laws of motion • The velocity of an animat is crucial. Recall that velocity is a vector , meaning it has both magnitude and direction . A steering force is also a vector, which when added to the animat’s existing velocity, will change its speed and direction. • We continually compute new steering forces to control movement existing motion steering force resulting motion

Slide3Steering, seeking and fleeing• Velocities and steering forces are both limited at some maximum value truncate(steering_force, MAX_STEERING_FORCE) //cap force to max velocity = velocity + steering_force; // accumulate vectors to get new vel truncate(velocity, MAX_VELOCITY) //cap animat speed to max Motion->move(velocity) //use interface to locomotion layer to apply the new vel • This can be the basis of other behaviours such as seeking , or moving to a target: compute a steering force that turns an animat toward some target. • The desired force is computed from the distance and bearing to the target and relative to the existing velocity of the animat • It is well to slow the animat down as it approaches a target because at maximum velocity it will overshoot and oscillate • Fleeing behaviour may be computed by simply negating the seeking vector, so that the direction of travel is away from the target existing motion steering force resulting motion

Slide4ICT2194 A Basic Obstacle-Avoidance Algorithm function avoid_obstacles2 check the Vision senses for free space in front, left and right if a frontal collision is projected (using Tracewalk) find the furthest obstacle on left or right determine the best side to turn towards compute the desired turn to seek the free space endif if the front obstacle is within a threshold distance proportionally determine a breaking force (slow down or stop) endif if there is an obstacle on the left side proportionally adjust the steering force to step right endif if there is an obstacle on the right side proportionally adjust the steering force to step left endif apply steering and breaking forces end function avoid_obstacles2

Slide5ICT2195 Knowledge Representation - Basics • In AI (and human) problem-solving, it matters a great deal how a problem is represented. Knowledge representation is the question of how human knowledge can be encoded into a form that can be handled by computer algorithms and heuristics • Knowledge representation languages have been developed to try to make representations as expressive , consistent , complete and extensible as possible • An ideal representation would - involve a good theory of intelligent reasoning - provide symbols that served as adequate surrogates for objects, events etc in the world - make ontological commitments (about what objects exist, and how to classify them) - provide data structures which can be efficiently computed - provide data structures which human beings can express all kinds of knowledge

Slide6ICT2196 Knowledge Representation - Basics need • We have already discussed one KR issue – whether knowledge should be encoded declaratively or procedurally (almost certainly need both) written • The notation of a KR is the symbols and syntax – what is written down or what • The denotation is the semantics, what the symbols refer to, or what you can do with them notation • In most KR, knowledge is a mixture of explicitly represented notation , and implicit knowledge available via inference • There are a lot of unanswered questions about how to gather, organise, store and use knowledge-bearing data structures • There is also a lot of research devoted to the processes (algorithms or heuristics) by which knowledge-bearing data structures can be manipulated

Slide7ICT2197 Formalisms • Symbols – we already use representations in basic programming left_obstacle_distance = 4.0; // distance to left obstacle is 4 units left_obstacle_colour = ‘’blue’’; // colour blob there is in the blue left_obstacle_identity = ‘’unknown’’; // nothing from the recogniser though right_obstacle_distance = 12.0; // distance to left obstacle is 4 units • Object-attribute-value To avoid the need to create many objects, attributes are represented as functions with two parameters: A(o,v) distance (left_obstacle, 4.0); //note - implicitly egocentric distance (right_obstacle,12.0); colour (left_obstacle, blue); • More natural since most attributes would be fetched from the world by a function

Slide8ICT2198 Formalisms • Frames – are a labelled package of slots, each with a value. The values might be pointers to other frames, or actors, which may launch procedural code frame_left_obstacle: distance: (4.0) colour: (blue) identity: (frame_fountain) on_proximity: <avoid_right 50.0f> • Semantic Networks – graphs with nodes representing entities linked by arbitrary relationships Tweety Bird Living_Thing Perch Cage Door Container Inanimate is-a is-a has-part has-part supported-by is-a is-a Yellow colour

Slide9ICT2199 Formalisms • Conceptual Graphs – more compact and flexible than semantic networks. Relationships get the status of nodes, and is-a links are made implicit • The graphs are suited to the expression of commonsense notions. The above graph represents the deep meaning underlying the sentence “Sue is quickly eating a pie.” • Conceptual graphs can also have actors, like frames • Such graphs can be manipulated according to canonical truth- preserving algorithms . These operations allow reasoning to carried out in terms of the graphs

Slide10•Rules – antecedent clause (condition) related to a consequent clause (action) by implication if (A and B) THEN S 1 • Antecedent clause is a boolean expression (possibly containing AND OR and NOT). Consequent clause can be any assertion or function call • Fuzzy rules – rules containing fuzzy logic terms (see later) • Subsymbolic patterns - eg networks with numerically weighted links Formalisms eg. Bayesian network • None! eg sensori-motor behaviours reacting directly to the world

Slide11ICT21911 Knowledge Engineering • Specification procedure – effort to pin down a rather scruffy kind of knowledge engineering suitable for novelle game AI • Sketching – informally draft some ideas about how to encode the important data structures and methods. - input (which inputs are available, which are needed, in what form?), - output (what primitive motor actions are needed?) and - context (what goes on behind the interfaces, what variables are involved, how can things be simplified?). • Formalising – the rough design is refined towards a formal specification for programming ie properly documented • Rationalising - The representations are tested for consistency, so that the parts will interoperate, with each other and with existing machinery • This processes is very creative and may loop back (like the Software Development Life Cycle)

Slide12ICT21912 Rule Based Systems - Basics • This is a real success story of AI – tens of thousands of working systems deployed into many aspects of life • Terms: a knowledge-based systems are really anything that stores and uses explicit knowledge (at first, only RBSs, later other kinds of system); a rule-base system (or production system) is a KBS in which the knowledge is stored as rules; an expert system is a RBSs in which the rules come from human experts in a particular domain • Can be used for problem-solving, or for control (eg of animat motion) • In an RBS, the knowledge is separated from the AI reasoning processes, which means that new RBSs are easy to create • An RBS can be fast, flexible, and easy to expand

Slide13ICT21913 RBS Components • Working memory – a small allocation of memory into which only appropriate rules are copied • Rulebase – the rules themselves, possibly stored specially to facilitate efficient access to the antecedent • Interpreter – The processing engine which carries out reasoning on the rules and derives an answer • An expert system will likely also have an explanation facility - keeps track of the chain of reasoning leading to the current answer. This can be queried for an explanation of how the answer was deduced. • Thus unlike many other problem-solving AI modules, an expert system does not have to be a “black box” ie it can be transparent about how it arrives at answers

Slide14ICT21914 Rule Based Systems - Architecture EXPLANATION FACILITY Keeps a trace of chain of rules for the current solution optionally

Slide15ICT21915 Rule Based Systems – Forward Chaining • To reason by forward chaining , the interpreter follows a recognise-act cycle which begins from a set of initial assertions (input states set in the working memory) and repeatedly applies rules until it arrives at a solution ( data driven processing) • Match – identify all rules whose antecedent clauses match the initial assertions • Conflict resolution – if more than one rule matches, choose one • Execution – the consequent clause of the chosen rule is applied, usually updating the state of working memory, finally generating output

Slide16ICT21916 Rule Based Systems - Backward Chaining • In backward chaining , the interpreter begins from a known goal state and tries to find a logically supported path back to one of the initial assertions ( goal-directed inference ) • Match – identify all rules whose consequent clauses match the working memory state (initially the hypothesised goal state) • Conflict resolution – if more than one rule matches, choose one • Execution – the state of working memory is updated to reflect the antecedent clause of the matched rule en D

Slide17ICT21917 Rule Based Systems – Conflict Resolution • The interpreter must choose one path to examine at a time, and so needs a method of conflict resolution in case of multiple rules • Methods include: - first come, gets served: choose the first rule that applies - rules are ordered into priorities (by expert): choose the highest rank - most specific rule is chosen: eg, apply the rule with most elements in antecedent - choose a rule at random, and use that - keep a historical trace, and allow this to chose a different rule next time • If the first chosen rule leads to a dead end, it should be possible to try another, provided a trace is kept • Note that this is another example of search through a graph of possibilities

Slide18Rule Based Systems - DevelopmentExplanation Facility • The process of encoding human knowledge into an expert system is called knowledge elicitation • It can be quite difficult to elicit expert knowledge from experts - they might not know how they know - they are very busy people – can’t get their attention for long - some knowledge might be difficult to codify as rules - different experts might disagree on facts and methods - facts and methods may change => need to maintain the system • Programmer may customise an expert system shell

Slide19ICT21919 Synthesising Movement with an RBS • Champandard describes a RBS system which implements wall- following behaviour: 1. If no wall is present and the animat was not already following one, move forward by a random amount 2. If a wall ahead is detected, the animat should turn away, neglecting any following of a wall at the side 3. If there is a wall to the side and not at the front, it should be followed by moving forward 4. If no wall is present and one was being followed, the animat should turn towards the side where the wall was last detected • 1 and 4 are similar, but depend on what the animat has been doing, thus a purely reactive agent cannot generate this behaviour • But an RBS can; it can use an internal symbol to remember what the animat has been doing • In a control system forward chaining used rather than backward chaining (why?)

Slide20ICT21920 How to Declare the Rulebase • The contents of the working memory and the rulebase is defined in XML <memory> <Symbol name=" sideWall " /> <Symbol name=" turnTowards " value=" false " /> ...... ...... </memory> <rulebase> <Rule> <conditions> <Symbol name=" following " value=" false " ground=“ true ”/> <Symbol name=" frontWall " value=" false " /> <Symbol name=" sideWall " value=" false " /> </conditions> <actions> <Symbol name=" following " value=" false " /> </actions> </Rule> ........ ........ ... other rules... ........ </rulebase> } rule base, condition-action pairs conjunction (AND) between clauses is implicit more than one action is allowed here default values are called ‘ground’ } working memory, set values, defaults

Slide21How to Use the Rulebase Interface• Native symbols must be synchronised so as to relay input from sensors into the RBS system at runtime • Register a variable declared in the working memory XML by SetSensor( &SensorSideWall, ‘’sideWall’’); //&Sensor.. is pointer to C++ var • This variable is now synchronised with the one in the working memory • We can use Get and Set accessor methods to fetch and change the values in working memory: void Set (const string& symbol, const bool value ); //sets a native var bool Get (const string& symbol) const;// returns boolean state of the var • Actions are implemented as functors (classes that store functions). Each action can then be a method in the same class. The C++ native variables can also be included for convenience. • You can even add rules dynamically – not recommended to begin with!

Slide22ICT21922 How the RBS Simulator Works • FEAR has a RBS simulator in the ‘modules’ directory • The working memory and rulebase set up with appropriate XML • Needs native functions linked to sensors and effectors • Interpreter (used for animat control) cycles through these steps: 1. Update working memory variables from inputs using CheckSensors(); 2. Scans rules (top to bottom), looking for a match using ApplyRules(). Rules that do not match are skipped. If all rules match, the defaults are applied, then overridden by rule specifications. If no matches are found, the default values are applied. 3. Effector symbols are scanned by CheckEffectors(), and native function calls are made if any are true. • Calling the function Tick() executes one such cycle • Once the system has been set up, most of the modifications can be done by just modifying the rules (provided they don’t need new sensors and effectors)

Slide23ICT21923 Back into Quake 2 • The Stalker demonstration animat uses these methods to implement wall-following • Study this carefully in the laboratory this week, using Champadard’s Chapter 12 as your guide

Slide24Summary• Steering behaviours are computed vectors which when added to existing velocity of an animat changes its motion in a realistic way • Knowledge representation is about how knowledge can be encoded into a form that can be handled by computer algorithms and heuristics • There are a lot of unanswered questions about how to gather, organise, store and use knowledge-bearing data structures • Classical AI formalisms for KR include simple symbols (variables), object-attribute-value A(o,v), frames, semantic networks, rules and fuzzy rules • In the Computational Intelligence approach, KR representations are subsymbolic, meaning numerical, and not explicit, so they cannot be read (by humans) • In Nouvelle AI, we might try to get by without knowledge representation at all (or at least take a minimal approach) • Rule-based systems use rules (antecedent-consequent pairs) as the basic unit of knowledge for problems solving, or control

Slide25ICT21925 Summary • An RBS contains a working memory, a rulebase and an interpreter • Input fact or states of affairs are asserted into the working memory. These are matched to rules in the rulebase. Matched rules fire, asserting new facts into the working memory which in turn fire new rules • When multiple rules might fire at once, a method of conflict resolution must be provided • The interpreter may work by forward or backward chaining • Expert systems get their rules from human experts and may have another component, called an explanation facility which provides a trace of the logical steps to reach a conclusion • It can be quite difficult to elicit expert knowledge from experts • FEAR has an RBS simulator which can be used for control of an animats behaviour, such as wall-following

Slide26ICT21926 References Reynolds, C. W. Steering Behaviours for Autonomous Characters. Proceedings of the 1999 Game Developer’s Conference , 1999, 763-782. Davis, R., Shrobe, H. & Solovits, P. What is Knowledge Representation? AI Magazine , 1993, 14, 1, 17-33.

![Exploring [Topic]: Answers, Facts, Opinions, and Resources](/thumb/20000800/exploring-topic-answers-facts-opinions-and-resources.jpg)